[column2]

In today’s society the speed of communication has reached its peak. In addition to the normal means of broadcast, we also have social networks. We can go on-line any time we like, anywhere we like and this has increased the number of users and the spread of global brands and chains of every type. Communication has become everyday, instant and occurs in real time. Thanks to internet people can divulge all kinds of information – where they will spend the evening, what they are cooking or where they are spending their holidays. People can share a song, an article about politics – even photos of the changes their bodies go through during pregnancy. Internet is used to alarm “friends” about children spotted on buses with fake parents, or make provocative statements.

In today’s society the speed of communication has reached its peak. In addition to the normal means of broadcast, we also have social networks. We can go on-line any time we like, anywhere we like and this has increased the number of users and the spread of global brands and chains of every type. Communication has become everyday, instant and occurs in real time. Thanks to internet people can divulge all kinds of information – where they will spend the evening, what they are cooking or where they are spending their holidays. People can share a song, an article about politics – even photos of the changes their bodies go through during pregnancy. Internet is used to alarm “friends” about children spotted on buses with fake parents, or make provocative statements.

These news items often provoke strong reactions and can spiral out of control, pushing people to refuse the news and run away from their responsibilities. Social networks therefore, have a limited capacity of communicating unpleasant information in a durable way. Paedophilia, mistreatment, the exploitation of children, sexual violence, incest, the slave trade and other issues are more widespread than we are led to believe. The result of the divulgation of this type of news- before and after- does not change.

Broken hearts, broken lives and broken bodies increase rather than decrease. In contrast however, the message inherent in the work of art remains indelible. In my opinion this is what drives Fatima Messana’s work. Messana is a young artist who has recently finished her studies at the Florentine Academy and is the winner of the first prize in sculpture at the X edition of the PNA held in Bari in 2013. She has a strong, determined personality and a sunny disposition. She began showing in 2003, and tells of the violence towards children and implicitly, of the impotence of those whose duty it should be to stop these shameful acts. Messana does not use filters – her message is totally clear in its expression of the monstrous acts Man is capable of and the horror Man produces. In «Innocence» (2008) violence has been inflicted on a thin childish body, pained, stricken and totally impotent.

There are no visible injuries, but the presence of the crucifix is an immediate symbol expressing torture and sacrifice. The feet hang loose, the hands are tied and the pubic area is uncovered. The realism of the work, made in fibreglass and painted in oil, is made more violent by the presence of the long hair which is real. This type of communication can seem crude, but it serves the artist’s intention to involve the spectator and provoke thoughtful reflection. Fatima’s views are very clear: “Man is a tamed beast and his mind is a dangerous thing, an apocalyptic box he looks into and where he sees reflected the depths of his own being .- what he cannot control is used against those who are defenceless. The purity of an infant is what distinguishes him/her from the masses who merely survive. A child who is robbed of his/her innocence is able only to survive, by attempting to wipe out what has made him/her cold and violated, condemning him/her to the indelible memory of his/her crucifixion.”

In the contemporary, international, artistic landscape Messana is not alone in using the figures of infants to denounce crime. The public is often violently upset by the artist’s choices – which are brutal and anguishing. However, it is important to point out that the artist is certainly not the criminal who offends the common sense of respect for a young life. It is the artist who is screaming her pain – pain which is unfortunately widespread globally. The second work presented by Fatima at “Il Cassero” is a female figure dressed in papal attire. The sculpture has never been shown before. It was completed in 2014 and can be seen here for the first time. The title «Testiculos qui non habet Papa esse non posset», is taken from the “Virility test” by Francesco Sorrentino, regarding the episode linked to the legend of the female Pope Joan who, in the mid IX Century, faked her way to becoming Pope under the name of John VIII. However, when she became pregnant, she was unmasked and stoned to death.

An essential part of the legend is a rite invented by the people and taken up by Sixteenth Century protestant writers with glee. It was imagined that new Pope underwent an accurate intimate exam to make sure he was not a woman dressed up as a man. The exam took place with the new Pope sitting a stride a crimson chair which had a hole in it. The youngest deacons present had to feel under the chair in order to make sure that the Pope possessed the necessary manly attributes. Since the XIX Century this event has interested writers and artists. In recent years two directors have brought the episode to the big screen. Even this work portraying the woman at the head of the Church as a static and austere form – faceless and without identity – is to be interpreted as a further criticism of the artist of the existing exclusion of women from positions of power, which have been traditionally seen as the domain of men for centuries. The figure blesses the population with one hand and wears the papal ring: with the other hand the figure holds the globe. The symbols are traditional except for the cross hanging around the figure’s neck – it does not have the crucified Christ, but shows a female figure.

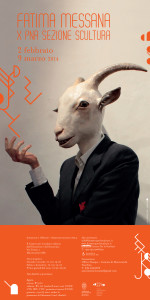

The third and last work on show is «Capra!» (Goat!) (2012).

This is the sculpture that won first prize at the X edition of the PNA in 2013. It is shown at “Il Cassero” in the miscellaneous hall, surrounded by portraits of the permanent collection with which the sculpture seems to speak. It is the bust of a man with a goat’s head made in fibreglass and fabric. The polychrome of this work, which characterizes all the works on show, is a result of the need for realism and linked to the ancient pictorial technique practised by the artist. The idea was inspired by the exclamation “Goat!” pronounced and repeated by Vittorio Sgarbi, a famous art critic who repeats the word “Capra!” (“Goat!”) insistently and at length every time someone disagrees with him. The word “Capra!” indicates Man’s ignorance, lack of basic truth and lack of knowledge.

Therefore it is clear that “Capra!” is the manifestation of Man’s refusal to see the horrors which afflict contemporary society. However, the presence of the Red Lion, symbol of the Venice Biennial present on the pocket of the figure’s jacket gives the work another dimension. The figure denounces the system and the target this time seem to be the Art world- especially the world of official, international shows. These are elite places where talent is not always necessary in order to become famous, and where money interests and business deals dominate, even though they have little to do with genuine artistic creativity.

The work has an apparently ironic form but, in reality, it is also representative of an existential condition in which the visible is illusionary and misleading. According to Schopenhauer the illusion covers the face of things, hiding their true authentic nature. According to Pirandello external reality , despite being unique and unchangeable, hides one hundred thousand realities – as many as there are people who invariably hide behind a mask.

The works of Fatima Messana come from the profound need to communicate social unease: her sculptures are “direct” and strongly conceptual or, as she loves to define them, pure visions, expressions which rise independently from her inner life.

[/column2]

[column2_last]

[flexislideshow pageid=”301″ lightbox=true lboxtitle=true slideshowtitle=true]

Nell’epoca in cui viviamo la rapidità della comunicazione è salita ai vertici della società, e ai normali mezzi di trasmissione si sono aggiunti i vari social network. La possibilità di accesso alla rete in qualsiasi momento e da ogni luogo ha favorito la crescita numerica degli utenti e la diffusione di marchi industriali globali e locali di ogni tipologia. Pertanto la comunicazione è divenuta quotidiana, istantanea e soprattutto trasmissibile in tempo reale. Con internet l’uomo può diffondere notizie di vario genere: dove passerà la serata, cosa sta cucinando, dove è in vacanza, condividere una canzone, un articolo di politica, fino ad arrivare a mostrare il cambiamento del proprio corpo in gravidanza.

Mediante internet allarma gli “amici” su avvistamenti di bambini in autobus con falsi genitori, o denuncia delicate questioni a volte provocatorie. Tali argomentazioni non passano inosservate, ma lo sconcerto che producono, seguito dalla scandalizzazione eventuale, portano in molti casi a rifiutare le notizie e a fuggire dalle proprie responsabilità. Dunque, i social solo limitatamente riescono a comunicare in maniera duratura informazioni scomode. Pedofilia, maltrattamenti, sfruttamento minorile, violenza sessuale, incesto, commercio di bambini e tanto altro, sono questioni non sufficientemente trattate rispetto alla loro reale diffusione.

Il risultato, prima e dopo la divulgazione della notizia non cambia, si aggiungono, invece di diminuire, cuori dilaniati, vite spezzate, corpi trafitti e vite bruciate. Diversamente, il messaggio insito nell’opera d’arte rimane indelebile. Sono questi a mio avviso i motivi sottesi alla ricerca di Fatima Messana, giovane artista che ha recentemente terminato l’Accademia fiorentina e vincitrice del primo premio di scultura al X PNA tenutosi nel 2013 a Bari. Personalità forte, determinata e solare, Fatima, la cui attività espositiva inizia nel 2003, racconta della violenza sui bambini e, implicitamente, della complice impotenza di chi dovrebbe impegnarsi per arrestare tale vergogna.

Messana non usa filtri, il suo messaggio esprime in totale chiarezza la mostruosità di cui è capace l’uomo, l’orrore che riesce a produrre con pochi gesti. In «Innocence» (2008) la violenza è inflitta ad un esile corpo infantile, stremato dal dolore e impotente. Non vi sono ferite visibili, ma la presenza del Crocifisso è un simbolo immediato che esprime tortura e sacrificio. I piedi penzolano, le mani sono legate e il pube è scoperto. Il realismo dell’opera, realizzata in vetroresina e dipinta ad olio, è reso ulteriormente violento dalla presenza dei lunghi capelli veri. Il modo di comunicare può sembrare crudo, ma in funzione della volontà dell’artista di coinvolgere l’osservatore e indurlo a ragionare.

Il pensiero di Fatima al riguardo non lascia fraintendimenti: «L’uomo è una belva addomesticata e la sua mente è cosa pericolosa, una scatola apocalittica dove egli si specchia nel fondo dell’essere e ciò che non riesce a controllare lo può riversare a discapito di chi non ha difese. La purezza di un infante è ciò che lo contraddistingue dalle masse informi degli uomini che vivono sopravvivendo. Una bimba derubata dalla sua innocenza non può far altro che sopravvivere, tentando con forza di cancellare ciò che l’ha resa gelida e violata, condannandola a portare con se il ricordo indelebile di ciò che l’ha messa in croce».

Nel panorama artistico internazionale contemporaneo la ricerca artistica della giovane artista non è isolata, anche altre personalità utilizzano figure infantili per denunciare ogni tipo di crimine a loro danno, e se, il più delle volte, il pubblico rimane violentemente turbato dalle scelte rappresentative dell’artista – così dirompentemente brutali e angoscianti – è da ribadire che il criminale che offende il comune senso del rispetto per una vita in crescita, non è certo l’artista, che invece urla un disagio atroce, tristemente diffuso a livello mondiale.

La seconda opera presentata da Fatima al “Cassero” è una figura femminile in abito papale. La scultura è un inedito, terminata all’inizio del 2014 ed esposta qui per la prima volta. Il titolo «Testiculos qui non habet Papa esse non posset», tratto da “Prova di virilità” di Francesco Sorrentino, riguarda la vicenda legata al mito o alla leggenda della Papessa Giovanna che alla metà del IX secolo salì, tramite inganni e travestimenti, al soglio pontificio con il nome di Giovanni VIII, ma rimasta incinta, venne smascherata e lapidata a morte.

Parte essenziale della leggenda è un rito fantasticato dal popolo e ripreso, in chiave anti-chiesa romana con molto gusto, da autori protestanti del Cinquecento: s’immaginò che ogni nuovo papa venisse sottoposto a un accurato esame intimo per assicurarsi che non fosse una donna travestita.

L’esame avveniva con il nuovo papa assiso su una sedia di porfido rosso, nella cui seduta era

presente un foro. I più giovani tra i diaconi presenti avrebbero avuto il compito di tastare sotto la sedia per assicurarsi della presenza degli attributi virili del nuovo papa.

A partire dal XIX secolo la leggenda ha interessato numerosi scrittori e in anni recenti ben due registi ne hanno narrato la vicenda sul grande schermo.

[…]Quest’opera raffigura una donna a capo della Chiesa, e in forma statica e austera, priva di volto e quindi identità, è da intendere come un’ulteriore riflessione critica dell’artista: la preclusione ancora esistente per le donne all’accesso di incarichi – pochissimi per altro – ancora esclusivi e secolarizzati per il genere maschile.

La figura con una mano benedice il popolo e indossa l’anello papale, mentre con l’altra sostiene il globo. I simboli sono tradizionali ad esclusione della croce appesa al collo, dove non c’è il Cristo crocifisso, ma un corpo femminile.

La terza ed ultima opera in mostra è «Capra!» (2012) scultura con la quale Messana vince il primo premio al X PNA del 2013. Esposta al Cassero nella sala miscellanea, attorniata dai ritratti della collezione permanente con i quali sembra dialogare. Si tratta di un busto d’uomo con testa caprina, realizzato in vetroresina e stoffa. La policromia di quest’opera, che caratterizza tutte le sculture in mostra, è data dalla necessità di realismo e legata all’altra tecnica praticata dall’artista, quella pittorica. L’idea prende spunto dalla prolungata e ripetuta esclamazione – Capra! – pronunciata dal critico e storico dell’arte Vittorio Sgarbi. Tale critica è stata più volte mossa, durante alcune discussioni, contro coloro che sostenevano idee a lui contrastanti.

Lasciando a ciascuno il giudicare tale l’atteggiamento, la parola “capra” indica l’ignoranza, la mancanza di fondamento veritiero e l’assenza di sapere dell’uomo. In quest’ottica «Capra!» è la manifestazione del rifiuto, da parte dell’umanità, di conoscere i drammi sociali che affliggono il nostro contemporaneo, ma allo stesso tempo, la presenza del leone rosso, simbolo della Biennale di Venezia, presente sul taschino della giacca della figura, orienta l’opera ad un’altra interpretazione di denuncia del sistema, e questa volta il bersaglio pare il mondo dell’arte, specificatamente quello delle esposizioni ufficiali e internazionali, luoghi elitari e circoscritti dove non sempre è la bravura a prevalere e ad essere riconosciuta, bensì fattori commerciali e mercantili, talvolta profondamente estranei alla genuina creazione artistica.

L’opera ha una forma apparentemente ironica ma, in realtà, è anche rappresentativa di una condizione esistenziale, nella quale il visibile è ingannevole ed illusorio. Secondo la filosofia di Schopenhauer infatti, l’illusione copre il volto delle cose, velando la loro essenza autentica, o come riteneva Pirandello, la realtà esterna pur essendo unica ed immutabile, nasconde centomila realtà, tante quante sono gli individui, i quali si nascondono dietro una maschera.

Le opere di Fatima Messana nascono dall’esigenza profonda di comunicare il disagio sociale, sono sculture “dirette” e fortemente concettuali o, come lei ama definirle, visioni pure, espressioni che sorgono autonomamente dalla sua interiorità.

[/column2_last]